The latter immediately conjures images of Donald Campbell and the ill-fated Bluebird K7 hydroplane hurtling along Coniston Water in the Lake District. The K7 ultimately resulted in Campbell’s death in 1967 as he tried to better his own record of 276mph (445kph). Despite the tragedy, the K7 remains one of the most successful water speed record boats of all time, with a legacy that continues to be held in the highest regard.

Campbell’s water speed record (WSR) stood for just six months after his untimely passing beaten first by American, Lee Taylor in the Hustler by less than 10mph and then again in 1978 by Australian, Ken Warby in the Spirit of Australia, which set the current record at a blistering 318mph.

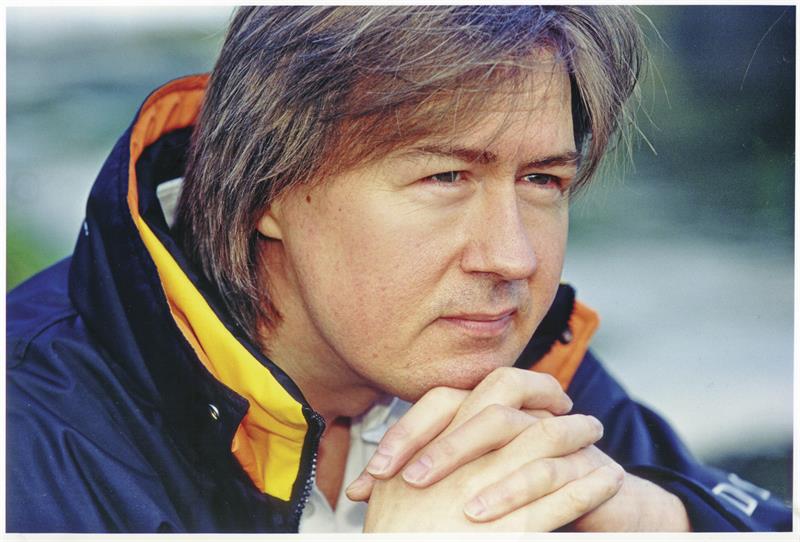

Enter technical author turned engineering entrepreneur Nigel Macknight, who both leads a record attempting development and also plans to pilot the hydroplane he calls, Quicksilver.

"It’s like climbing Everest, the challenge is there and that makes you want to do it," says Macknight. "And I certainly feel we should get the record back for Britain."

There is a poignant and tangible link between Campbell and Macknight. Bluebird K7’s co-designer, Ken Norris, partnered with Macknight in 1988 to design a boat capable of challenging for the record.

"Ken had an idea for a new boat before Donald was killed," recalls Macknight. "It was an enticing idea to develop the Bluebird that never was. Who wouldn’t be allured by that?"

It proved, however, a frustrating partnership as the catastrophe of the K7’s demise haunted progress with one iteration quickly following another, and the direction for the overall design constantly changing. Macknight, desperate for progress, decided it was time to go it alone in 2001.

Hydroplane design

As a boat increases speed, its hull rises up and begins to skim across the water’s surface. Rather than buoyancy, hydrodynamic lift becomes the predominant upward force on the hull as it begins ‘planing’.

As a boat increases speed, its hull rises up and begins to skim across the water’s surface. Rather than buoyancy, hydrodynamic lift becomes the predominant upward force on the hull as it begins ‘planing’.

"Water is 800 times the density of air, so the further out of the water you can get the less drag there will be and the faster we’ll be able to go," explains Macknight. "But, therein lies the danger. If you come out too far, you’ll go the whole hog, like Campbell, and the boat will flip over.

"You want a skinny boat with very little of what’s called ‘kite area’ at high-speed as you don’t want the air to get hold of the boat, lift it up and flip it over. But at low-speed, around 50mph, that hull shape is totally unsuitable as there’s very little area to lift the boat up. You really want two different hulls, one for 50mph and one at 350mph."

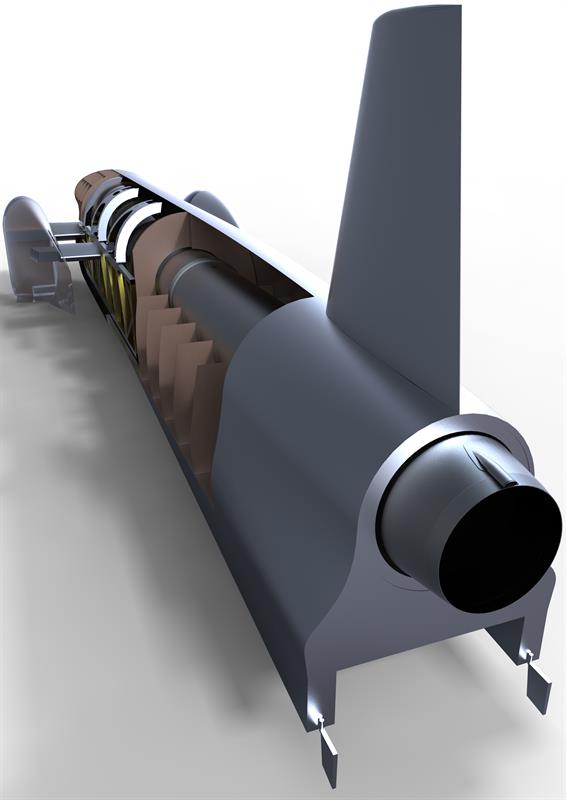

There is still a tangible amount of DNA that can be traced back to Norris’s original designs and even to Bluebird before that. The engine, for example, is the same 10,000hp Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan. And after three decades, the design and development of Quicksilver has made real progress. Its main hull is a space frame made of high-tensile steel tubing. Bolted on that frame is a fabricated aircraft-grade aluminium upper-hull structure with the rest of the boat mostly made from lightweight core materials such as Airex and Baltek sandwiched between Kevlar and carbon fibre skins.

One major innovation is the decision to have four points of contact with the water during planing. This is a marked move away from conventional hydroplane speedboats that typically use a three-point configuration. While the extra contact increases drag, critically it offers greater stability at higher speeds.

"When you look at Quicksilver, it’s like looking at Bluebird," says Macknight. "It’s just a bigger, heavier, more powerful, four-point version of Bluebird. So we’ve come full circle."

Quicksilver uses floats known as sponsons to provide buoyancy at low-speed as well as stability at high-speed. These are critical components and their positioning has always been hotly debated. "If you look at the final design of the Bluebird K7, it had the sponsons at the front," says Macknight. "At that time, one of the things that Ken agonised over was whether to have them at the front or back. Today, I’m certain it’s the front."

Another major design consideration is achieving the best compromise between low-speed efficiency and high-speed stability. Aerodynamic and hydrodynamic design is vital here with a delicate balance necessary between the two.

Assembly of Quicksilver is currently underway with the main body of a steel space frame incorporating a Rolls-Royce turbofan engine.

Making a run

To the layman, ideal conditions for a record breaking run might seem to be during benign weather and flat calm waters. However, if the water is too calm it is difficult for the boat to ‘unstick’ from the surface and rise up onto its planing surfaces. Not only will the water’s surface be subject to whatever waves, swells and other disturbances exist on the day, but the boat itself will be a major influence as it passes through. And like the land speed record, an official WSR requires a pass in both directions, within 60 minutes – meaning any water disturbance from the first pass is likely to affect the second run.

One area where Quicksilver is different from any other boat that has attempted a WSR is in the level of information that can be gathered about high-speed dynamic behaviour. With extensive data recording equipment, sensors and telemetry, the team hope to be able to thoroughly understand the stability of the boat through its speed range.

"We’ll be able to gather data on all kinds of things as we go up to 350mph," says Macknight. "Irrespective of whether we get a record or not, we’re actually creating a very exciting and useful hydrodynamic research project.

"Although the record is the icing on the cake, and it’s the ultimate goal, there’s something worthwhile happening all along the way; we’re building up a huge resource in terms of unique knowledge, data and experience."

In general, any speed record attempt is usually a long, drawn out development, against near impossible odds. Like the other current speed record contenders in Bloodhound and Triumph, Quicksilver rouses deep imagination and excitement amongst its peers. However, record attempting runs always seem one or two years away, as is the case for Macknight and Quicksilver. But, like all things, it only remains impossible until it’s done.

"There is no doubt, this is an extremely difficult thing to achieve," says Macknight. "But this has been my calling and I’m driven by the genuine belief that I can get the record."

| Nigel Macknight Leaving school with a handful of qualifications, Nigel Macknight became a successful technical author writing books on rockets, spacecraft, aircraft and Formula One. Clearly, the fringes of engineering possibility have always been an allure. As a teenage friend to Bluebird designer Ken Norris, Macknight rekindled this relationship in the 1980s after hearing Norris planned to develop a successor to the Bluebird K7 hydroplane. Despite not having an engineering background, his self-belief and determination to make the project happen has seen him continue the work to design, make and pilot Quicksilver. "I’ve had to become an entrepreneurial, engineering project manager and showman," he says. "If you look at Donald Campbell and Richard Noble, they don’t fit the mould. Both had almost no experience when they started out, but had plenty of determination and self-belief." Hear from the man himself at this year's Manufacturing and Engineering North East (MENE) Show. |

| The legacy of Donald Campbell and his design team

Behind his success were chief designer Ken Norris and brother Lew Norris. The design and engineering of the Bluebird K7 was a revolution at the time. It’s three planing points were arranged with two forward, on outrigged sponsons and one aft, in a "pickle-fork" layout, prompting Bluebird’s early comparison to a blue lobster. Its load bearing steel space frame was ultra-rigid and stressed to 25g, exceeding contemporary military jet aircraft. Campbell set seven world water speed records in the K7 between July 1955 and December 1964. The Norris brothers also designed the Land Speed record holding Bluebird-Proteus CN7, which in 1964 set a new record of 403mph. The Norris brothers are the only engineers that designed and developed both land and water speed record holding vehicles. |

The Quicksilver team is made up entirely of skilled volunteers. If YOU want to get involved and help achieve the next World Water Speed Record find out more and

get in touch at www.quicksilver-wsr.com

Donald Campbell’s name became synonymous with speed records in the 1950s and 1960s as he broke eight world speed records on water and land. He remains the only person to set both the world land and water speed records in the same year (1964).

Donald Campbell’s name became synonymous with speed records in the 1950s and 1960s as he broke eight world speed records on water and land. He remains the only person to set both the world land and water speed records in the same year (1964).