In an engaging historical coincidence, it is befitting that Heliex Power is developing its steam technology only a few miles south of Glasgow, where James Watt adapted the early promise of steam 335 years ago, to build the foundations of the industrial revolution.

Like Watt, whose gifts included being able to identify weaknesses in a system and to improve them, Heliex has technology that remedies one of the great problems in modern industrial processes – that of waste. In particular waste steam.

The technology was initially developed at City University in London and taken on by spin-out company Heliex in 2010. City University had been looking at improving screw air compressor technology - an electric motor driving two screws taking ambient air and sending it out at a higher pressure. Heliex’s chief executive, Chris Armitage, explained the background: “They said what if we looked at the whole thing the other way round, if we took some sort of fluid and expanded it through these screws the other way round, could we not drive, use the machine to drive something else, such as a motor turning into a generator?And the obvious first fluid to consider for doing that is steam, because it's well known for driving turbines and the like.”

The steam used in power stations is ‘dry’ steam, in that it is superheated so it contains no condensate particles of water, which is the more familiar ‘wet’ steam we see coming out of kettles. Wet steam both contains less energy than dry, and is too corrosive on standard turbine blades.

Armitage outlined the Heliex system: “What we've got in a twin screw is a more robust, simpler piece of equipment, which will accept wet steam without being eroded. It therefore can be used in the vast majority of steam systems in factories and process plants who only have saturated steam. They don't have superheated steam, because it's so much more costly to produce, and they just don't need it.”

This is not aimed at power stations, although there may be applications within power stations it can be used, it is aimed at general industry, any process that uses steam directly as part of the process or has a steam system used as a heating medium. Or even a waste heat stream that could be used to generate steam. With such a wide range of potential uses Heliex believes there could be a huge market for the technology.

“We need to have some reasonable pressure differential to generate power,” said Armitage. “We've got to have a minimum of seven or eight bar gauge pressure. But the flow rates are not particularly huge.The higher the flow rate, the greater the power output, but under reasonable pressure drop and three tonnes an hour of steam, we can produce a reasonable power output that's of interest to a customer.”

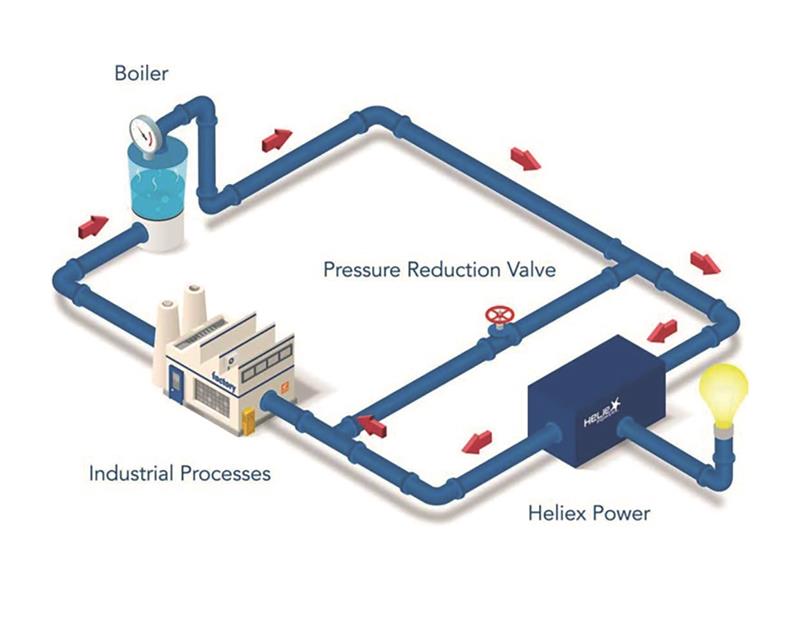

In fact, some industrial users are perfect in that they already generate steam in a boiler, but it comes out at much higher pressure than they can use in their process, so they pass it through a PRV – a Pressure Reducing Valve. The Heliex machine can sit across the PRV and bring the system pressure down to required levels and generate electricity in the process.

Armitage described the machine itself: “The core of it and the clever bit, is the screw expander, which is very similar to a screw air compressor in that there are two rotors entwined with each other. The profile of the rotor is the important part, those two rotors sit within a casing and supported on bearings at each end.We expand the steam through that expander and in doing so, the two rotors turn and we have an output at one end. We connect that to a generator to produce electricity.” Around those two fundamental pieces of equipment, there are some ancillaries; an oil system for lubricating the bearings, an inlet control valve to control the amount of steam, and a control panel that controls the system and the interconnection with the grid, because generally power will be exported to the grid.

There are two patents, one is around the profile of the rotors. Armitage described one: “The important thing is how, as the rotors turn, the edge of the rotors don't actually touch, but they do form a seal between themselves with a very small piece of water, which is where the wet steam is useful.” There is also a patent, held by City University, for the use of this machine in a thermodynamic (Rankine) cycle.

So how does the Heliex system counter the erosive nature of wet steam. Armitage said: “It's a combination of the way the steam is put into the machine, the profile of the rotors, and the rotors are also just a much more robust piece of equipment than a relatively thin turbine blade. The profile of the inlet port ensures that we get maximum efficiency on the machine, but also ensures that the steam expands in a manner that is more conducive to it not eroding the rotors.”

The rotors are nitrided to improve corrosion resistance, but the casing does not need to be particularly resilient and is a standard casting.

Next stage in development is to effectively turn the system round the other way – using a motor to drive the expander to recompress steam in processes that don’t naturally condense steam. Armitage explained: “Starting with a low-pressure steam, typically it would condense that steam to water, then reheat it in a boiler and turn it back into steam at a higher pressure.So you've got the energy requirement to condense it in the first place, then the energy requirement to re-vaporise it into steam, both of which are a waste of energy, because you're putting it back to the state it was in. By using our machine, you just take the steam and increase its pressure with an electrical input which is much more efficient.” It could also feasible that the expander could be used to drive other bits of equipment, like a pump or air-compressor, rather than a generator.

Currently there are two sizes of expander feeding into a range of sizes of generator that vary between 75 kilowatts (for a 8bar, 2Tonne/hr of steam flow rate application) and 0.5 megawatt output (for a 25bar, 12Tonnes/hr). They are both the same in terms of velocity and basic design. Systems could cost from £100,000 up to £500,000.

Already the company has over 40 installations. Armitage concluded: “We do a lot within the biomass industry, but they are actually producing heat for many, many other industries. So we've got units in steel manufacture, glass manufacture, in nurseries, on the back end of incinerators.So there's a whole range of industrial processes that use steam in one way or another.”

Operating conditions

|