Since water-resistant standards play a big role in making expensive handheld and wearable digital devices more durable, the industry has adopted the IPX7 rating, which protects against immersion in water for 30 minutes at a depth of 1m.

Yet the critical element in meeting or exceeding these higher standards is something most consumers are barely aware of—micro fasteners that must lock out moisture while also complementing the aesthetics of the phone, watch or tablet design. Making devices that are eye-catching as well as water, air and dustproof adds incredible value to a product.

Fulfilling both demands is proving difficult because some of the most effective processes for making large, practical screws are not suitable for micro fasteners, experts say. As a result, the cost per unit is two or three times higher for the smaller screws. In addition to this, in some cases, overspray of the sealant needed to assure water resistance has led to a discolouration that ruins the appearance of the device’s exterior.

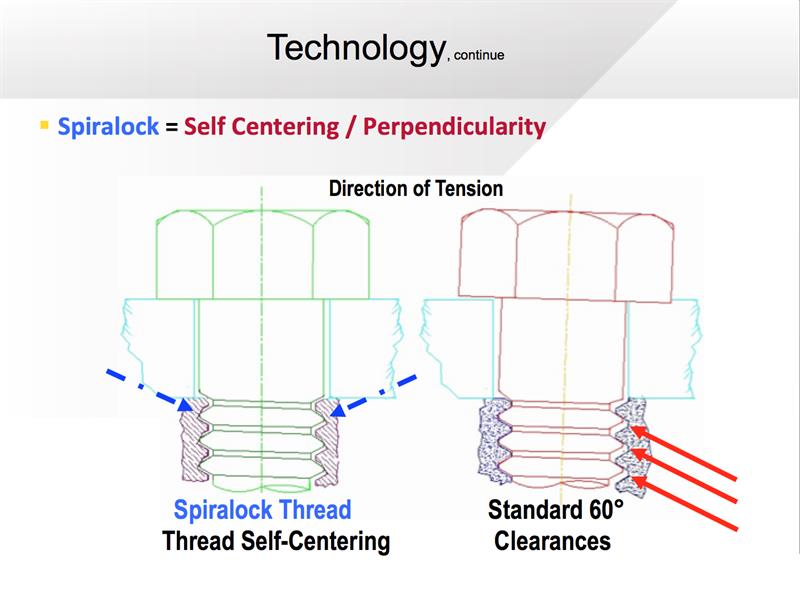

Compared to traditional screws, the Spiralock thread profile is self-centring and the head of the fastener is perpendicular to the bearing surface.

Compared to traditional screws, the Spiralock thread profile is self-centring and the head of the fastener is perpendicular to the bearing surface.

Testing for a solution

A solution that improves reliability while lowering costs was discovered using a variable water pressure simulation chamber where a combination of water and air pressure simulates 1 to 10m of water depth. The assembly was conducted using guidelines set by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) using a minimum of 32 pieces (in this case the M1.0 x 3.0, a common sized screw used in digital devices).

Initially, the screws were tightened to the correct seating torque specifications using a micro torque wrench (ISO threads = 0.36Kgf-cm; threads = 0.42Kgf-cm. A 15% increase in torque was added to the threads in order to achieve the same clamp load due to friction.) Water pressure was applied to the head of each fastener to simulate an actual environment that could destroy a portable electronic device (such as a toilet, swimming pool or bathtub).

Once the chamber achieved full pressure, engineers set a timer for 30 minutes and then closely watched the pressure meter and checked for leaks in the dry bottom portion of the chamber. If the pressure dropped and/or the presence of water was found on the bottom test plate, this would indicate a system failure. The test was created and executed by Sean Riskin, director of engineering for the Global Electronics Group at STANLEY Engineered Fastening. Afterwards, he created a revealing study that includes his findings that tested nearly a dozen fastener configurations of various brands to find the best solutions that meet or exceed IPX7 standards.

Most sealants for micro fasteners are a nylon or Teflon-based substance and there are only two options for applying the protection. Manufacturers either seal the threads or seal underneath the head of the screw. Both have advantages and disadvantages.

In at the deep end

Sealing just the threads may not protect the multiple layers of components that are in a typical fastened joint. This is because the components being fastened together are in the path of water before the protective sealant. Sealing under the head is preferable, because it is the first barrier against moisture. Yet this is the method that, in some cases, results in an overspray and discolouration caused by the application process.

“You don’t want to spend double or triple the price on a fastener and not have it look cosmetically pleasing,” Riskin says. “In a sense, electronics manufacturers are struggling with a three-way battle; function versus beauty versus cost.”

Also, the sealant is what creates prohibitive costs because it must be applied to every single unit as a secondary operation, forcing major manufacturers to spend millions of pounds annually just on micro fasteners alone.

But what if the sealant could be eliminated from the equation? That’s easier said than done. Here, the sealant creates a water and dust barrier, and, in addition, the screws must have an anti-vibration feature applied, so that it won’t loosen or back out during normal use. Both features are second and third operations that are very costly to the overall price of a fastener.

The solution that Riskin was looking for came from the combination of under head design features of screws and Spiralock, a subsidiary of STANLEY, which had developed and re-engineered a female thread profile that adds a unique 30° wedge ramp at the root of the thread and mates with standard 60° male thread fasteners. This innovation removes the need for nylon-based patches or other anti-vibration countermeasures and therefore significantly reduces the cost of fasteners.

The M1 x 3 screw is commonly used in the assembly of digital devices

Mind the gap

Riskin’s study revealed other advantages, too. When torqued to specifications, standard screws are not perfectly perpendicular; most are a couple of degrees off-axis and therefore create a gap where fluid can enter. The Spiralock thread profile, in comparison, is self-centring and the head of the fastener is perpendicular to the bearing surface.

However, he knew that this alone would not entirely seal out moisture, so he added an 87° under head feature and semi-flat head to the micro fasteners. Although the head designs have been available for years, this is the first time they’ve been combined with Spiralock’s modified locking thread profile to create excellent moisture sealing joints that exceed the IPX7 rating standards.

It also creates a vibration-proof joint that is easy to assemble, thus saving digital device brands time and money. “When you’re stacking multiple components for assembly, tolerances always add up and nothing is perfect,” adds Riskin. “So, the more bearing surface area you have is a major advantage. These solutions provide additional bearing surface area or a single circular point of contact under the head, significantly improving the sealing surface.”

Now that his study is complete, he hopes his discoveries will help handheld and wearable device manufacturers dive deeper into the realm of new possibilities.

Riskin concludes: “Nobody wants to be just as good as their competition. They want to be better. Everyone is trying to get a piece of the market by diversifying themselves. That’s exciting. Imagine what we might be buying and wearing in a couple of years.”