It was an eye-catching sight with Froome crouched low on top of the frame of his bike with his body hunched over the handlebars. Two people that sat up and took notice were Thierry Marchal, global industry director for sports, medicine and construction at ANSYS and Bert Blocken professor of aerodynamics at TU Eindhoven and KU Leuven.

The pair have collaborated previously on work involving the aerodynamic benefit of riding in front of a team car or motorcycle. After a phone conversation discussing the media coverage of the ‘aerodynamic advantage’ that Froome had given himself to win the stage, the two sports fans decided to team up once more to find out firstly, if the position really was aerodynamically beneficial and, if not, what is the ultimate position for cycling downhill?

“This work was done not for a company or a team, we did it independently because we just wanted to know ourselves,” says Marchal. “We had no funding at all for this, the idea was just, let’s see out of interest what is actually going on with different positions.”

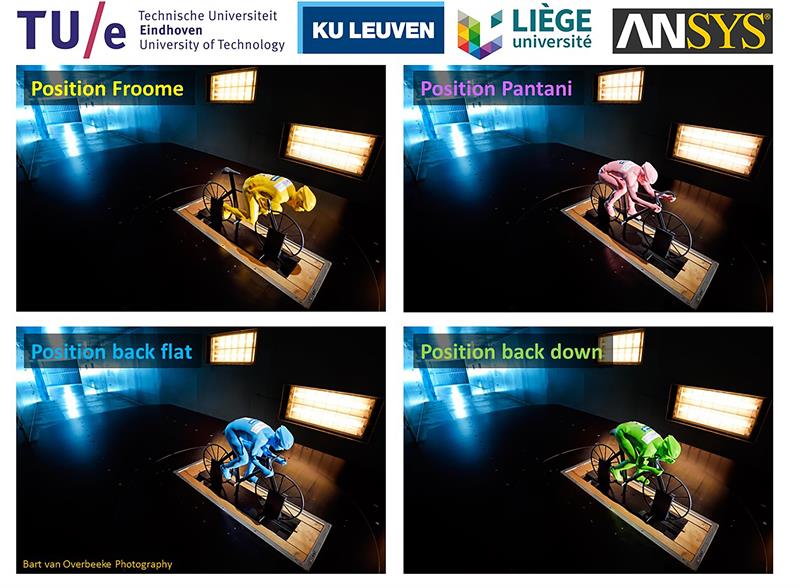

They created four models to test in the wind tunnel at the University of Liège in Belgium: Froome’s position; two more classic aerodynamic positions – one with the rider sat on the saddle with its back horizontal and one with its back positioned downwards with the head lower – and another unique position used by the Italian Marco Pantani in the 1990s where he had his chest on the saddle effectively hanging off the back of his bike.

They created four models to test in the wind tunnel at the University of Liège in Belgium: Froome’s position; two more classic aerodynamic positions – one with the rider sat on the saddle with its back horizontal and one with its back positioned downwards with the head lower – and another unique position used by the Italian Marco Pantani in the 1990s where he had his chest on the saddle effectively hanging off the back of his bike.

Blocken explains: “These [models] are four times smaller than reality, so to have the same physics the speed in the wind tunnel must be four times larger. Four times larger than 15m/s is 60m/s, that’s 216kph, which is a Category 4 hurricane. That’s why the moulds in the wheels have reinforcements, otherwise the models would just break in the wind tunnel.”

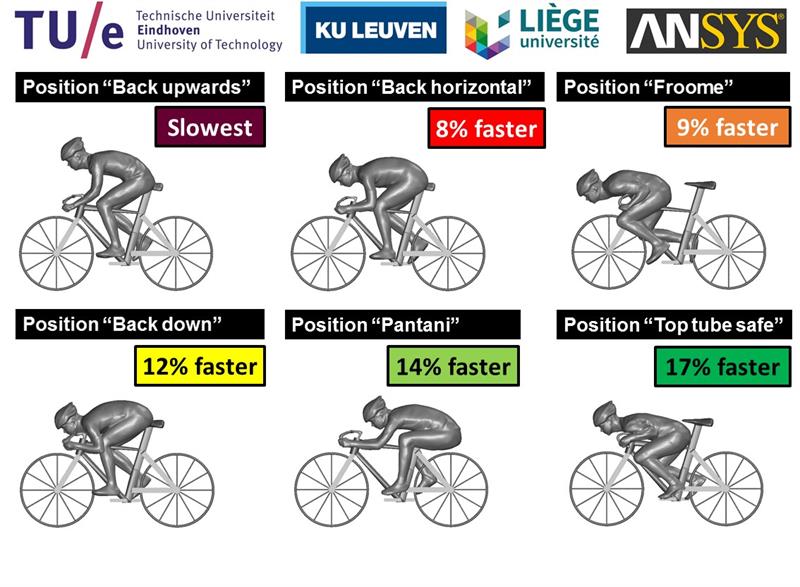

These models were tested against the ‘Froome’ position with the ‘Pantani’ position proving to be best aerodynamically, at 4.8% faster. Next fastest was the ‘back down’ position, which was 2.4% faster than the ‘Froome’ position, and finally the ‘back horizontal’ position, which was 0.5% slower.

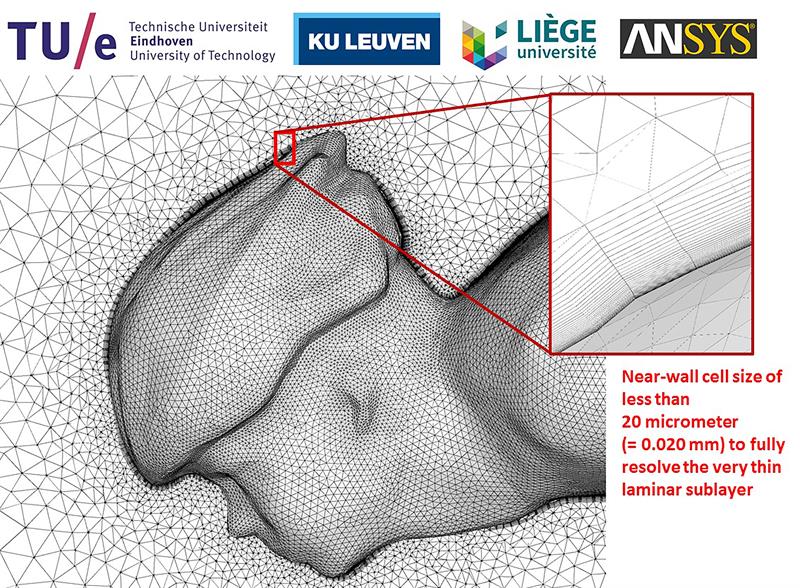

To be certain that the wind tunnel results were accurate, the models were scanned and tested independently using  ANSYS’ Fluent CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software. These computational models contained 36 million control volumes and are so detailed that the very thin layer close to the body called the laminar sublayer caused by hair on the skin of the cyclist was recreated. These features measure just 0.02mm but are critical to achieve accurate and reliable results.

ANSYS’ Fluent CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software. These computational models contained 36 million control volumes and are so detailed that the very thin layer close to the body called the laminar sublayer caused by hair on the skin of the cyclist was recreated. These features measure just 0.02mm but are critical to achieve accurate and reliable results.

This encouraged the team to add two more positions to be tested by CFD alone: a ‘back upwards’ position – the kind you may employ while cycling for fun; and ‘top tube safe’, where the cyclist has their body horizontal along the crossbar with their head just over the handlebars. What they found was that the upright position, unsurprisingly, was the slowest by a considerable margin, but the top tube safe position was the fastest of all, 3% faster than the Pantani position.

Marchal says: “If you had asked me before which of these four is the best, or the most aerodynamic, I would probably have guessed wrong even though I’ve been doing this kind of work for the last 20 years.

“It’s complicated and that keeps it interesting.”

This test was based on the 15.5km descent down the Col de Peyresourde at the average speed that Froome traversed it: 62.5kph and it assumes riders were of the same height, weight and had the same power output. If the slope was less steep and the cyclist needed to lay down extra power the ‘top tube safe’ and ‘Froome’ positions would both fall further down the list as it is more difficult to peddle in these positions while the ‘back horizontal’ position would move up.

This test was based on the 15.5km descent down the Col de Peyresourde at the average speed that Froome traversed it: 62.5kph and it assumes riders were of the same height, weight and had the same power output. If the slope was less steep and the cyclist needed to lay down extra power the ‘top tube safe’ and ‘Froome’ positions would both fall further down the list as it is more difficult to peddle in these positions while the ‘back horizontal’ position would move up.

Across the length of the 15.5km descent, a cyclist in the ‘top tube safe’ position would have pulled out a gap of 67s on Froome. ‘Back down’ would have gained 23s and ‘back horizontal would have lost 8s. However, the addition of peddling would have increased these times over the ‘Froome’ position as you can put more power through the peddles and the more even weight distribution gives better manoeuvrability and stability.

There is also the topic of safety to consider, something Marchal and Blocken are keen to highlight. “[The Froome position] is a dangerous position, putting a large weight on the front wheel, which is also the one you’re using to steer with,” explains Blocken. “Froome could do this on the Col de Peyresourde because it is quite a straight descent. Pantani put a large amount of weight on the back wheel, that is also not so stable, but in the others it’s actually quite an even distribution.”

When asked about Froome’s position, Team Sky’s sports director, Nicolas Portal says: “It looked a little dangerous when they sit on the frame, you can see the balance is not the best. You can see on TV the bike is really moving. But, the aero position is really good so they feel straightaway that they gain speed and momentum. Then when they lose momentum they need to start pedalling in this position. It looks a bit ugly, but when something works, that’s how it is.”

When asked about Froome’s position, Team Sky’s sports director, Nicolas Portal says: “It looked a little dangerous when they sit on the frame, you can see the balance is not the best. You can see on TV the bike is really moving. But, the aero position is really good so they feel straightaway that they gain speed and momentum. Then when they lose momentum they need to start pedalling in this position. It looks a bit ugly, but when something works, that’s how it is.”

Beyond the scientific results, Marchal and Blocken fear that professional or occasional cyclists might be putting themselves at risk by adopting dangerous positions in the hope of improving their aerodynamics. With the three major tours, the Giro, the Tour and the Vuelta, just around the corner, some may be tempted to adopt the ‘Froome’ position, which the researchers say takes a greater risk for less gain.

“We believe it is our responsibility to educate all cyclists, professional or occasional, about the actual benefits and limitations of each position,” Marchal says. “We also encourage professional cyclists willing to consider new positions to first approach us so that we could safely investigate them on the computer and in the wind tunnel before taking any risk on the road.”

This is a view backed up by Blocken who adds: “The final conclusion is that it is not necessary to take the most dangerous positions. It’s not the fastest, it’s not the safest and it’s not the one where you can generate the most power.”

Did Froome win the stage because of the position he adopted? Not according to the analysis. A more likely explanation is that there weren’t many riders in the chasing group who were in contention for the Yellow Jersey, especially at that early stage in the Tour, so why would they tire themselves out attempting to chase him down? In fact Froome could have crashed, throwing away the lead at any point during the descent by being unbalanced through the corners. Don’t try this at home.