What the manufacturers like Volvo, Jaguar Land Rover and VW (or at least what the headlines) didn’t say was that most of them would be moving into hybrid electrification of their vehicles, not fully-electric models. However, this still means that ICE efficiencies must be increased and emissions decreased to meet ever tightening regulations.

Cambridge based Camcon Auto is one such company looking to provide the most efficient electrically driven valvetrain possible. To do this, the company has replaced the camshaft with a set of electromagnetic actuators, a system it calls IVA (intelligent valve actuation).

Mark Gostick, Camcon Auto’s COO explains: “IVA replaces the conventional camshaft on an engine with a set of valves that are under digital control allowing infinitely variable control of timing, lift and period. It’s a concept to digitise the last remaining analogue system on an internal combustion engine which is the air charge. We like to think of IVA as engine breathing by wire.”

This infinitely variable control over the valves means that any load speed point in the engine’s range can be optimised whether for fuel consumption, NOx emissions, hydrocarbons, or running it during a cold start for instance, to maximise heat transfer to the exhaust to get the catalyst lit quickly.

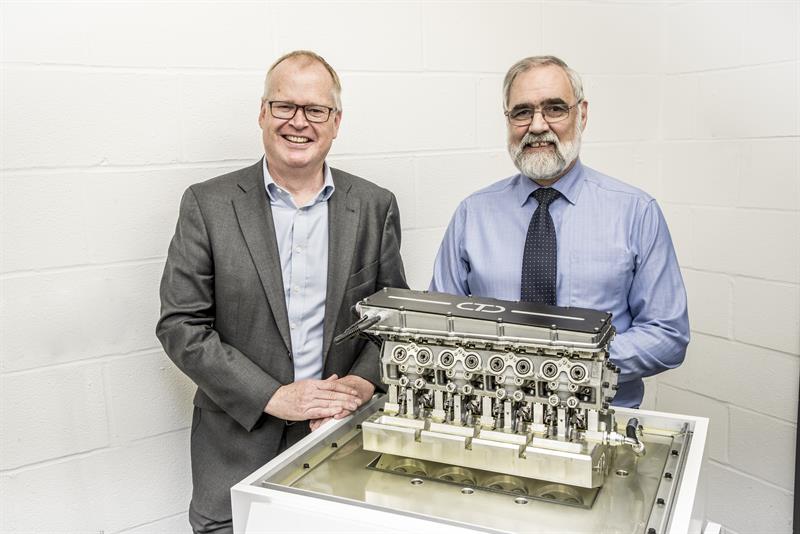

Mark Gostick (left) and Roger Stone of Camcon Auto

Using a new 2 litre, four-cylinder petrol engine given to them for testing by Jaguar Land Rover, Camcon’s technical director, Roger Stone says: “We’ve established the optimum valve events for those points and that has given us two results. One result is it can reduce CO2 emissions by around 15-20%, the other shows that what the engine wants is beyond the capabilities of any other single variable valve system. Even the most flexible of the current systems can only provide part of the requirements of what we’ve shown the engine wants. As well as reducing emissions we’ve improved power, reliability and performance.”

Previous work has been done in this area with ‘ballistic systems’ using two opposing large solenoids acting directly on the valves to open and close them. This system got to a very late stage of production before it failed.

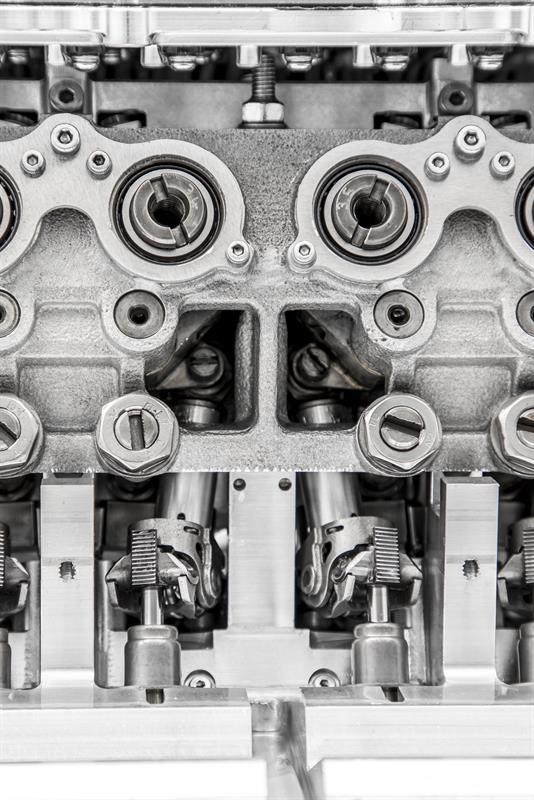

“There were a number of issues: noise, wear, and compared with what we can do the capability was significantly less,” says Stone. “We use a rotary actuator to operate a little mechanism that lifts the valve in a more conventional way, controlling the speed of the actuator and, by driving the individual camshaft arrangement for each valve, essentially tailoring the event.”

According to Stone, IVA has been designed to fit within a conventional engine package and to fit almost any engine and particularly suits hybrid engines. The full-feedback control gives a reduction on energy loss when stopping and re-starting the engine, which not only reduces CO2 emissions but also helps increase the range of electric motors. Alternatively, smaller, cheaper batteries could be used instead to keep battery range constant and bring down the overall cost of the vehicle, despite the IVA system costing more than a traditional camshaft.

According to Stone, IVA has been designed to fit within a conventional engine package and to fit almost any engine and particularly suits hybrid engines. The full-feedback control gives a reduction on energy loss when stopping and re-starting the engine, which not only reduces CO2 emissions but also helps increase the range of electric motors. Alternatively, smaller, cheaper batteries could be used instead to keep battery range constant and bring down the overall cost of the vehicle, despite the IVA system costing more than a traditional camshaft.

“There’s a significant package advantage in hybrids in that, if you use IVA on both the inlet and the exhaust, you can delete the timing drive altogether,” Stone explains. “Which means you’ve got more room for either a bigger electrical machine between the engine and the gearbox or you can fit a given hybrid powertrain package into a smaller vehicle.”

The big challenge for the design team was achieving the required torque density and timing control. The key enabler is Camcon’s proprietary Binary Actuation Technology (BAT). Stone explains: “Although the IVA employs a Desmodromic valve system, that in itself wasn’t the starting point, the fact that it employs a positive opening and closing mechanism lends itself to our application by maximising control system authority. It also helps minimise the actuator size and power demand.

“The starting point for us was the Camcon bi-stable actuator, a very low energy and fast actuator. Unlike a solenoid, it has two zero-power stable states whereas a conventional solenoid has only one, requiring power all the time, and an extra latching mechanism at the extreme of movement. The BAT system is fired from one end to theother withoutany separate latching and no power except during the switching operation.”

OEMs can even tune the system to meet their own specific balance between BMEP (Brake Mean Effective Pressure), emissions and fuel consumption at every engine speed and load condition. Plus, there is the potential to minimise knock by better control of residuals and of the effective compression ratio.

To achieve this, Stone says the VCU has to be significantly faster than any other controller currently in use on an engine: “It’s extremely important to get the controlling algorithms right. The system power consumption depends on the quality of that algorithm, and that’s an area we’re particularly active in at the moment. By automotive standards the VCU needs to be significantly faster than an ignition or fuelling ECU because we’ve got to be looking at where valve position may be 100 times per event, whereas a fuel/ignition ECU only has to do its sums once every other revolution for each cylinder. We’ve got a lot of computing to do; we’re talking about a 100-microsecond computing cycle.”

To achieve this, Stone says the VCU has to be significantly faster than any other controller currently in use on an engine: “It’s extremely important to get the controlling algorithms right. The system power consumption depends on the quality of that algorithm, and that’s an area we’re particularly active in at the moment. By automotive standards the VCU needs to be significantly faster than an ignition or fuelling ECU because we’ve got to be looking at where valve position may be 100 times per event, whereas a fuel/ignition ECU only has to do its sums once every other revolution for each cylinder. We’ve got a lot of computing to do; we’re talking about a 100-microsecond computing cycle.”

The system has been put through many hours on a dynamometer and has also been fitted to a vehicle for further development. However, commercialisation is not on the horizon yet.

Gostick says: “IVA has the potential to bridge the gap between petrol and diesel; offering diesel fuel consumption with petrol emissions performance and we believe that it can exceed all upcoming emissions legislation,” he concludes. “I think most of the manufactures, if you talk to them privately, recognise that the internal combustion engine has got a long way to go yet.”

Other applications The IVA system is currently being used in two other automotive applications. One is called ‘Park Lock’, where the vehicle’s transmission is locked when it is parked. The other is an ABS control mechanism for HGVs that can reduce either stopping distance or air consumption by about 20%. Outside automotive, the technology is being used by Silverwell Technology to enable low-power switching of very high-pressure gas into oil wells to increase the amount of oil being extracted. Camcon Medical is using the same approach in the metering of oxygen for patients on ventilators to save the two-thirds of oxygen wasted when patients are exhaling. There are also some early-stage applications being considered in the aerospace industry. |