The early part of 2018, however, has brought anyone harbouring such notions abruptly down to earth. Two high-profile fatal accidents involving autonomous vehicle technology have set its cause back to an extent that is hard to overstate.

The first took place in Tempe, Arizona on 19 March when 49-year-old Elaine Herzberg was hit and killed by an Uber vehicle in autonomous mode as she crossed a dimly-lit road at night. While the shockwaves of this event were being felt, on 23 March, the driver of a Tesla X died after the vehicle hit a central reservation on a California highway.

Clearly, the reasons for these tragedies are still under investigation. In relation to the accident, however, the president of the company that builds Uber’s lidar sensors, Marta Hall of Velodyne, has said of its use of a single 360º system on the car’s roof: “If you’re going to avoid pedestrians, you’re going to need to have a side Lidar to see those pedestrians and avoid them, especially at night.”

Meanwhile, UK company Aptiv, which makes the standard collision-avoidance technology in the Volvo SUV used by Uber has made it clear that its systems were switched off when the fatality occurred and that the Volvo XC90’s standard advanced driver-assistance system “has nothing to do” with the Uber test vehicle’s autonomous driving system.

In the case of the California incident, Tesla has pre-empted the investigation by releasing a certain amount of information unprompted.

In the case of the California incident, Tesla has pre-empted the investigation by releasing a certain amount of information unprompted.

In its statement, it said: “In the moments before the collision, which occurred at 9:27 a.m. on Friday, March 23rd, Autopilot was engaged with the adaptive cruise control follow-distance set to minimum. The driver had received several visual and one audible hands-on warning earlier in the drive and the driver’s hands were not detected on the wheel for six seconds prior to the collision. The driver had about five seconds and 150 meters [sic] of unobstructed view of the concrete divider with the crushed crash attenuator, but the vehicle logs show that no action was taken.”

In its statement, Tesla also claimed that driving a Tesla equipped with Autopilot hardware, meant drivers were 3.7 times less likely to be involved in a fatal accident. However, as far as public confidence is concerned, the damage has already been done. Chris Jones, co-founder of technology analyst Canalys says: “It has put the industry back. It’s one step forward, two steps back when something like this happens… and it seriously undermines trust in the technology. Tesla and Uber are disruptive companies who are trying to shake up the industry – and it’s an industry that needs shaking up – and it has been affected greatly by these two companies in the last few years. But unfortunately, it’s these two companies that have been most affected by these events.”

Jones, who specialises in the autonomous vehicle sector and launched his company’s Autonomous Vehicle Analysis service, sees these events as likely to set the industry back considerably. He says: “Many of the major automotive OEMs have shared their plans about when they intend to bring vehicles of a high level of autonomy to market over the coming years. This is a bit of a moving target and the incidents over the last few weeks could change things. Will they actually bring the vehicles to market that they say they will in the light of these events?”

Jones, who specialises in the autonomous vehicle sector and launched his company’s Autonomous Vehicle Analysis service, sees these events as likely to set the industry back considerably. He says: “Many of the major automotive OEMs have shared their plans about when they intend to bring vehicles of a high level of autonomy to market over the coming years. This is a bit of a moving target and the incidents over the last few weeks could change things. Will they actually bring the vehicles to market that they say they will in the light of these events?”

Even before these tragedies, the ecosystem for the autonomous vehicle sector was extremely complex and is changing dramatically. The past few years has seen the emergence of a number of start-ups in this industry, with OEMs in the middle. Most crucial, however, are the autonomous vehicle technology and solution providers – there are dozens of these. Says Jones: “They’re all chasing to be first. There’s a real race to get their platform on the road as soon as they can.”

Some of the key driving forces behind the industry are fleet management, on-demand car and ride sharing services such as Uber, Lyft and their Chinese equivalent DiDi. According to Jones: “These guys want to get rid of their drivers. And they are playing a key role in bringing autonomous vehicles to market over the next few years.” In fact, many OEMs – including GM, Ford and VW – are planning that ‘robotaxis’ will be the first of this type of vehicle to be trialled.

In general, Jones is sceptical about the pronouncements of manufacturers regarding when they will release autonomous vehicles, saying: “What does it actually mean when a company says it’s going to releasea certain vehicle in 2021? It could mean one model, one market. So, although they’re putting their stake in the ground, it might in fact be a very limited plan or limited volume.”

The potential wildcard, however, could be China. Says Jones: “The Chinese companies involved in this are treating it as a race. And that’s worrying. Because a company like Baidu – the Google of China – has a very aggressive plan and will try to do things as fast as it can.”

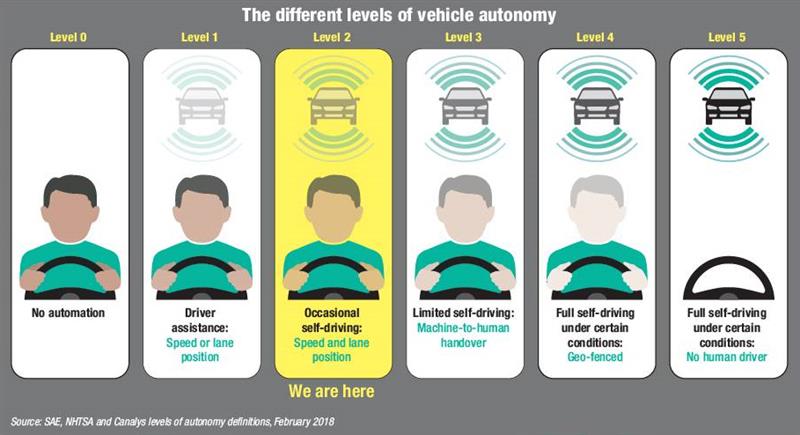

Regulation, however, represents the biggest potential stumbling block for the autonomous vehicle sector. At present, levels of vehicle autonomy are defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) from level zero to level 5, with level five meaning fully self-driving under all conditions. Currently, technology is at Level 2, which means occasional self-driving and adjustment for speed and lane position.

However, where things become most complex from a regulatory point of view is Level 3, since it is here that limited self-driving means the requirement for the vehicle to hand control back to the human driver in the case of circumstances it cannot deal with.

According to Jones (pictured above), this is leading a lot of companies to avoid this stage. “Audi is the first to have announced a Level 3 vehicle coming to market,” he says. “The thing is that you can’t do this until it’s regulated and the authorities have said they can definitely do this. This is because Level 3 requires a handover from vehicle to human in the case of an emergency. What will the human be doing when the vehicle needs the human to take over? How does one handle the handover?

That question really scares the industry and it’s why a lot of companies have decided to skip over Level 3 altogether.”